The FuelVM

Highlights:

-

The FuelVM serves as the core of the Fuel stack, informed by insights from various virtual machine designs like the EVM and Solana's SVM.

-

It supports state-minimized application development through features such as native assets and ephemeral scripting, promoting decentralized and accessible architecture.

-

The UTXO model facilitates parallelized transaction execution, enhancing throughput and reducing latency by allowing concurrent processing of non-conflicting transactions. The FuelVM is a register-based virtual machine, providing better performance compared to traditional stack-based designs and offering a structured instruction set for efficient operations.

-

Predicates, scripts, and contracts are essential components of the FuelVM, enabling flexible spending conditions, transaction processing, and state management within its execution environments.

The FuelVM lies at the core of the whole Fuel stack; it was created by taking into account years of learning from other virtual machine designs, like the EVM, Solana’s SVM and more.

The FuelVM enables developers to move away from stateful application designs often enabled by smart contracts by providing more feature-rich state-minimized facilities such as native assets, ephemeral scripting, and ephemeral spending conditions. By offering alternative methods for developers to build state-minimized applications, we enhance full node sustainability while maintaining a decentralized and accessible architecture, aligning with Ethereum’s core values.

In the following sections, we will discuss the key features of the FuelVM in detail.

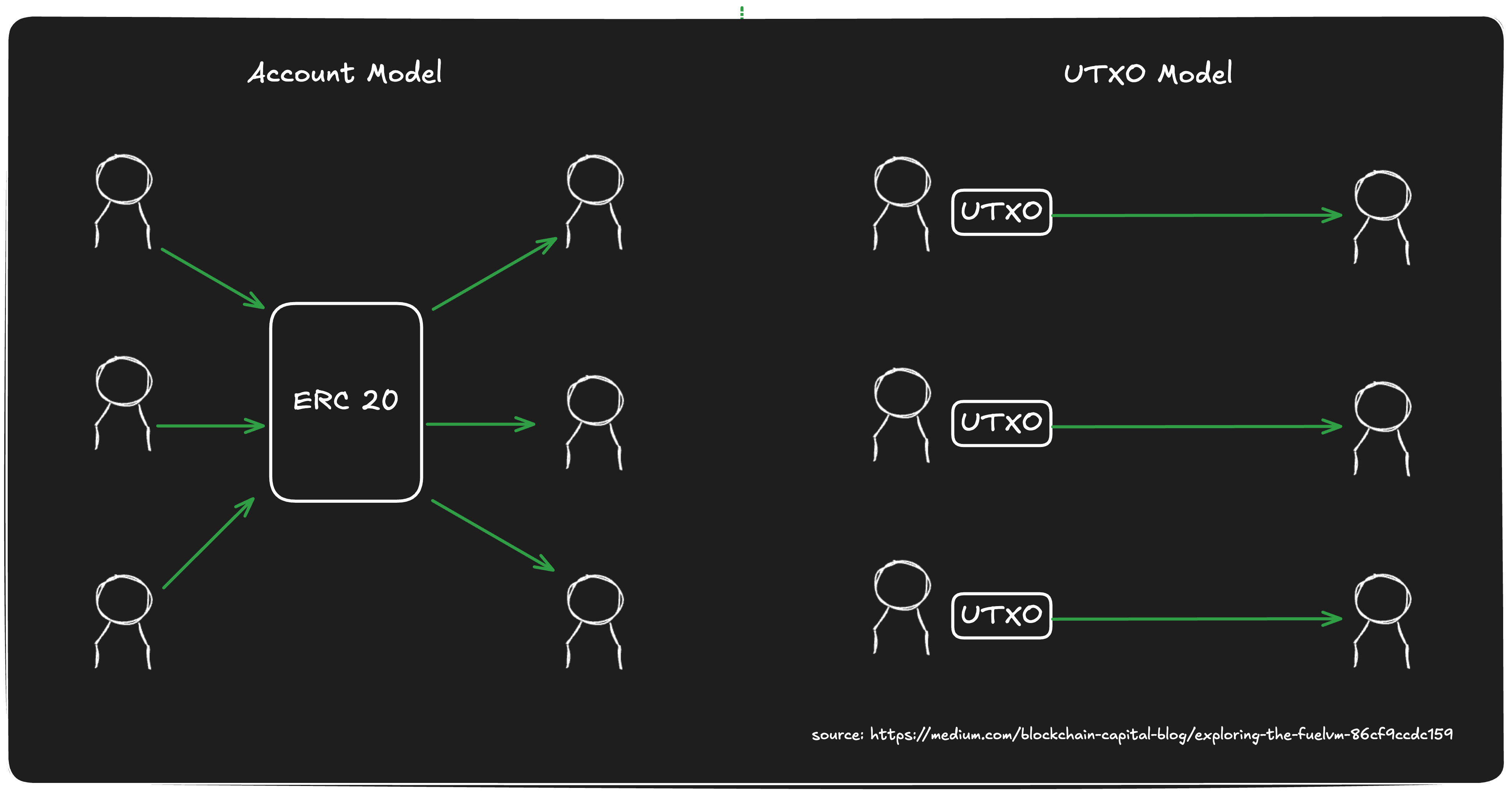

UTXO Model and Parallelization

Fuel’s parallelized transaction execution model serves as a cornerstone for its efficiency and scalability. Parallelization dramatically improves throughput and reduces latency compared to traditional sequential processing methods. It breaks tasks into smaller sub-tasks, executing them simultaneously across multiple processing units.

Parallelization is built upon a foundation of Access Lists and the UTXO (Unspent Transaction Output) model, which works in tandem to enable concurrent processing of non-conflicting transactions.

Our tech leverages the UTXO model for performing transactions on Fuel. Transactions modeled through UTXOs handle everything from token transfers to smart contract calls.

Addresses on Fuel own unspent coins, allowing them to spend and perform transactions through the FuelVM.

Using the UTXO model helps achieve transaction parallelization. At runtime, users provide the inputs and outputs for their transaction. Transactions without overlap process in parallel, enabling Fuel to scale horizontally with the number of cores per machine.

Register based design

The FuelVM operates as a register-based virtual machine, unlike the EVM and many others, which use a stack-based architecture.

Register-based virtual machines consistently outperform stack-based virtual machines.

The FuelVM includes 64 registers, each 8 bytes, with 16 reserved and 6-bit addressable.

| value | register | name | description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0x00 | $zero | zero | Contains zero (0), for convenience. |

| 0x01 | $one | one | Contains one (1), for convenience. |

| 0x02 | $of | overflow | Contains overflow/underflow of addition, subtraction, and multiplication. |

| 0x03 | $pc | program counter | The program counter. Memory address of the current instruction. |

| 0x04 | $ssp | stack start pointer | Memory address of bottom of current writable stack area. |

| 0x05 | $sp | stack pointer | Memory address on top of current writable stack area (points to free memory). |

| 0x06 | $fp | frame pointer | Memory address of beginning of current call frame. |

| 0x07 | $hp | heap pointer | Memory address below the current bottom of the heap (points to used/OOB memory). |

| 0x08 | $err | error | Error codes for particular operations. |

| 0x09 | $ggas | global gas | Remaining gas globally. |

| 0x0A | $cgas | context gas | Remaining gas in the context. |

| 0x0B | $bal | balance | Received balance for this context. |

| 0x0C | $is | instructions start | Pointer to the start of the currently-executing code. |

| 0x0D | $ret | return value | Return value or pointer. |

| 0x0E | $retl | return length | Return value length in bytes. |

| 0x0F | $flag | flags | Flags register. |

The FuelVM Instruction Set

The FuelVM instructions are 4 bytes wide and have the following structure:

- Opcode: 8 bits

- Register Identifier: 6 bits

- Immediate value: 12, 18, or 24 bits, depending on the operation.

The FuelVM instruction set has been documented in detail here: https://docs.fuel.network/docs/specs/fuel-vm/instruction-set .

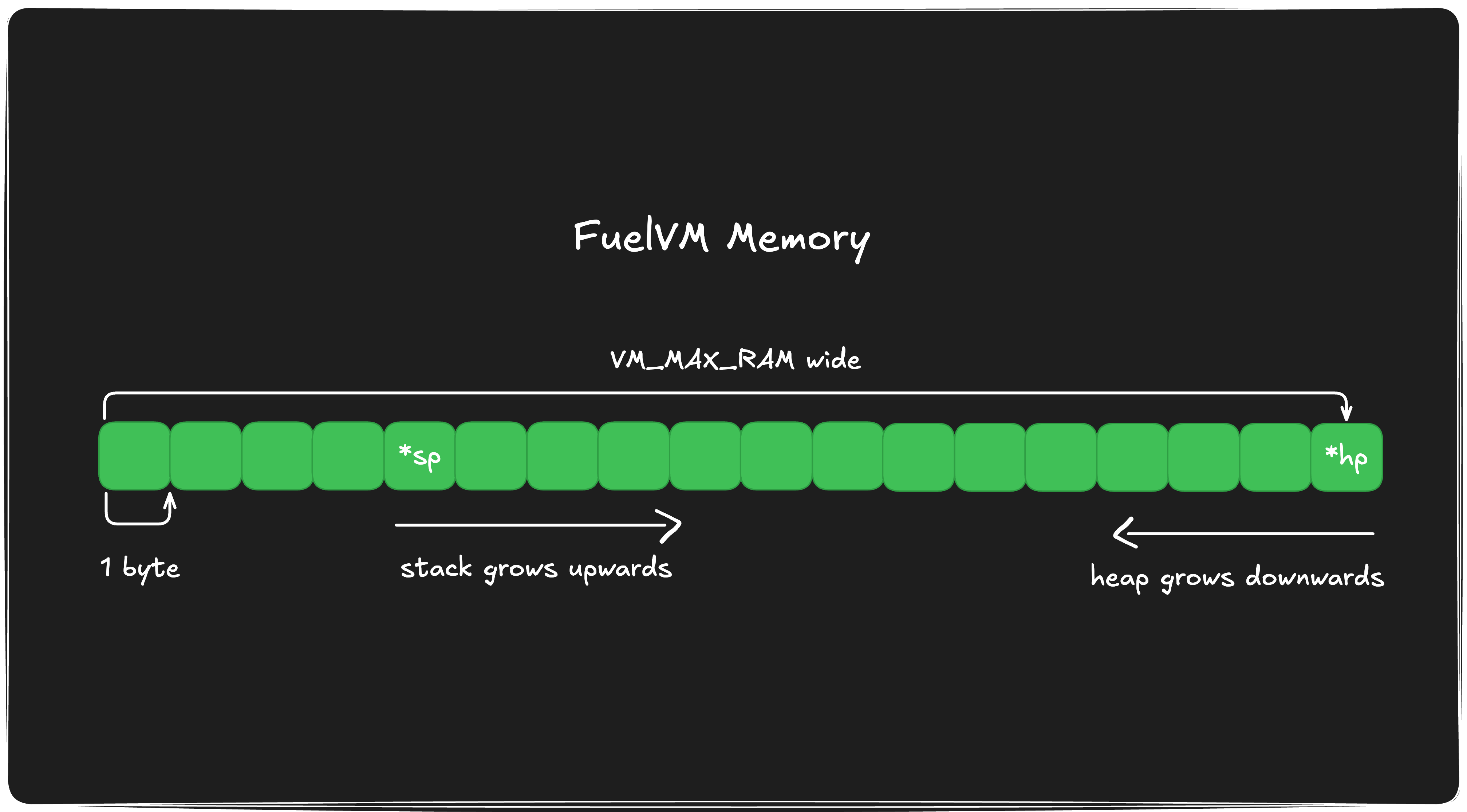

Memory

FuelVM uses byte-indexed memory, configurable with the VM_MAX_RAM parameter. Hence, each instance of FuelVM can decide how much memory it wants to allocate for the VM.

Memory follows a stack and heap model. The stack begins from the left, immediately after the initialized VM data and call frame in a call context, while the heap starts at the byte indexed by VM_MAX_RAM.

Each byte allocation on the Stack increases the stack index by 1, and each byte allocation on the heap decreases its writable index by 1. Hence, the stack grows upwards, and the heap grows downwards.

The stack and the heap have the following essential registers associated with them:

-

$ssp( 0x05 ): Memory address of bottom of the current writable stack area. -

$sp( 0x06 ): Memory address on top of current writable stack area (points to free memory). -

$hp( 0x07 ): Memory address below the current bottom of the heap (points to used/OOB memory).

The FuelVM has ownership checks to ensure that contexts have a defined sense of ownership over particular regions in the memory and can only access memory from the region they own. We will elaborate more on this topic in later sections.

Predicates, Scripts and Contracts

Understanding further concepts for Fuel requires grasping:

- Predicates

- Scripts

- Contracts

Let’s dive deeper.

Predicates

Predicates are stateless programs that define spending conditions for native assets. Native assets go to predicates, and to determine whether they are spendable in a transaction, the FuelVM executes the bytecode and checks the boolean return value. If the returned value is true, the asset can be spent; if the returned value is false, then the transaction is invalid!

People can program various spending conditions, such as spending only if three out of five approve a transaction or if a transaction includes specific desired inputs and outputs, commonly known as intents.

Predicates operate statelessly, without persistent storage, and cannot call other smart contracts.

Scripts

Scripts serve as the entry point for Fuel transactions, dictating the flow of the transaction. Like predicates, they lack persistent storage. However, they can call contract Inputs, which are part of the Fuel transaction and can have persistent storage of their own.

This enables Fuel to natively support advanced features such as multi-calls, conditional contract execution, and more.

Contracts

Fuel provides support for smart contracts in its UTXO model. Smart contracts are stateful and can be called by other contracts. In Fuel, smart contracts are represented by the InputContract type. To learn more, refer to the section on InputContract.

The first call to a contract in a transaction occurs through a script, after which the contract can call other contracts.

Contracts have persistent storage, a key-value pair of 32-byte and 32-byte values. Various data structures are being considered to determine the optimal approach for committing to contract storage.

Contexts

A context is a way to isolate the execution of various execution environments for predicate estimation and verification, scripts, and contracts. Each context has its memory ownership, which we will expand on later.

There are four types of contexts in Fuel:

- Predicate Estimation

- Predicate Verification

- Script Execution

- Calls

The first three are called External contexts, as the $fp is zero, while Calls are called Internal contexts and will have a non-zero value for $fp.

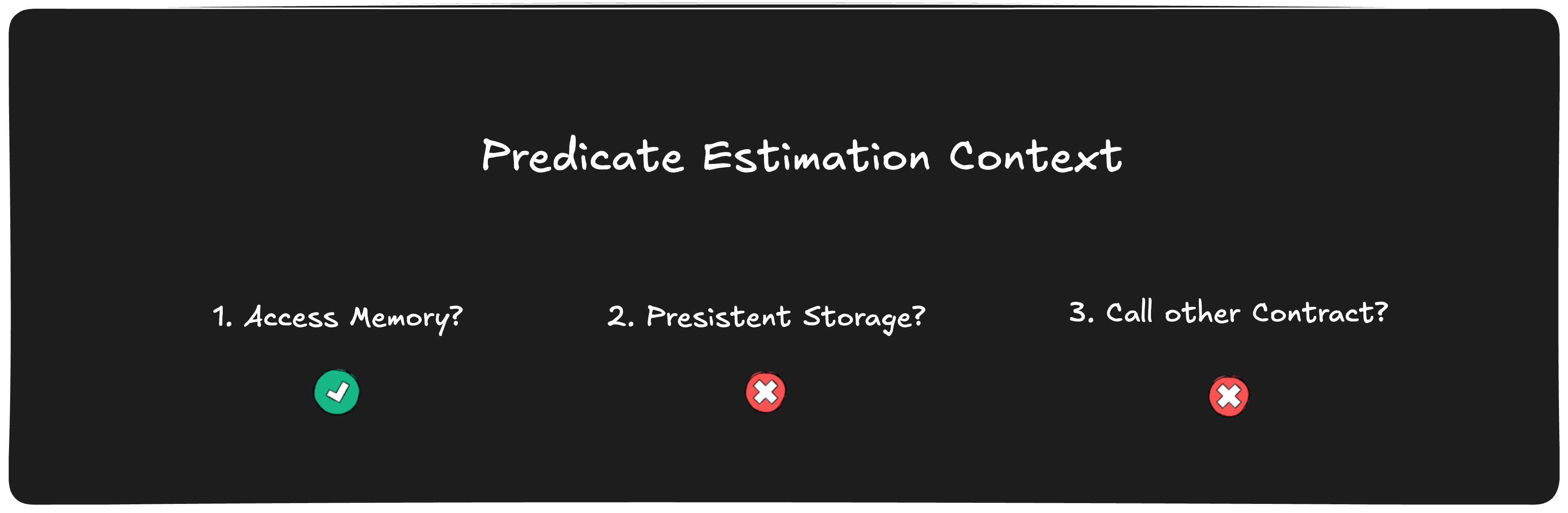

Predicate Estimation

Fuel transactions provide predicateGasUsed for each predicate used. During verification, if predicateGasUsed is less than the total gas consumed during verification, the transaction reverts.

The user performs Predictive Estimation locally or by calling a remote full node, which executes the predicate in the FuelVM and returns the total gas consumed.

Predicate estimation context cannot do persistent storage or make calls to Contracts.

Predicate Verification

All predicate parts of the transaction are verified to return true before executing the transaction script. The FuelVM is used in the Predicate Verification context when verifying a transaction's predicates.

Predicate verification context cannot do persistent storage or make calls to contracts.

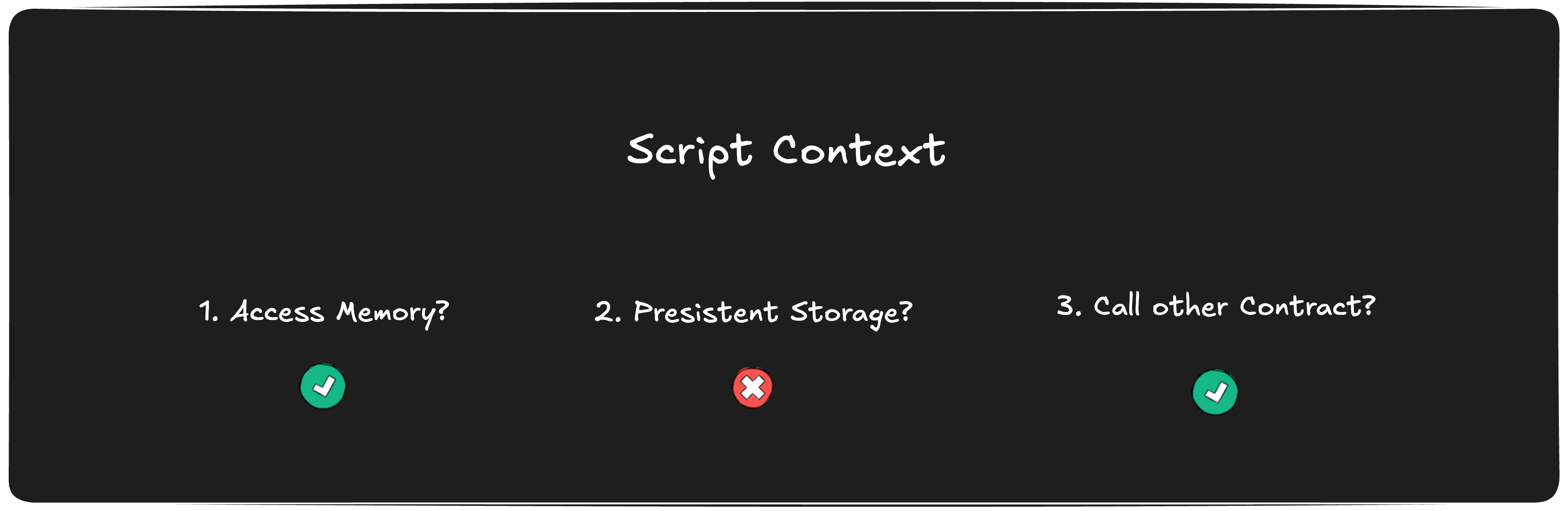

Script Execution

After verifying all predicates, the transaction script is executed; the script execution context cannot do persistent storage but can make calls to contract.

Calls

Call contexts execute contracts, offering flexibility, storing data persistently, and making contract calls.

Call context is created by either:

- Script calling a smart contract

- Contract calling a contract input

Each call creates a “Call Frame”, which is pushed to the Stack. A call frame holds metadata on the stack, aiding the execution of the call context in the FuelVM. A call context cannot mutate the caller's state and only access its stack and heap.

| bytes | type | value | description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unwritable area begins. | |||

| 32 | byte[32] | to | Contract ID for this call. |

| 32 | byte[32] | asset_id | asset ID of forwarded coins. |

| 8*64 | byte[8][64] | regs | Saved registers from previous context. |

| 8 | uint64 | codesize | Code size in bytes, padded to the next word boundary. |

| 8 | byte[8] | param1 | First parameter. |

| 8 | byte[8] | param2 | Second parameter. |

| 1* | byte[] | code | Zero-padded to 8-byte alignment, but individual instructions are not aligned. |

| Unwritable area ends. | |||

| * | Call frame's stack. |

After a call context has successfully ended, its call frame is popped from the stack. However, any space allocated on the heap during the execution of the call context persists in memory.

A call context returns its value using the $ret and $retl registers. Large return values can be written to the heap and later read from the caller contexts.

Memory Policies

After understanding the various contexts for executing the FuelVM, we now discuss the policies for reading and writing to memory in contexts.

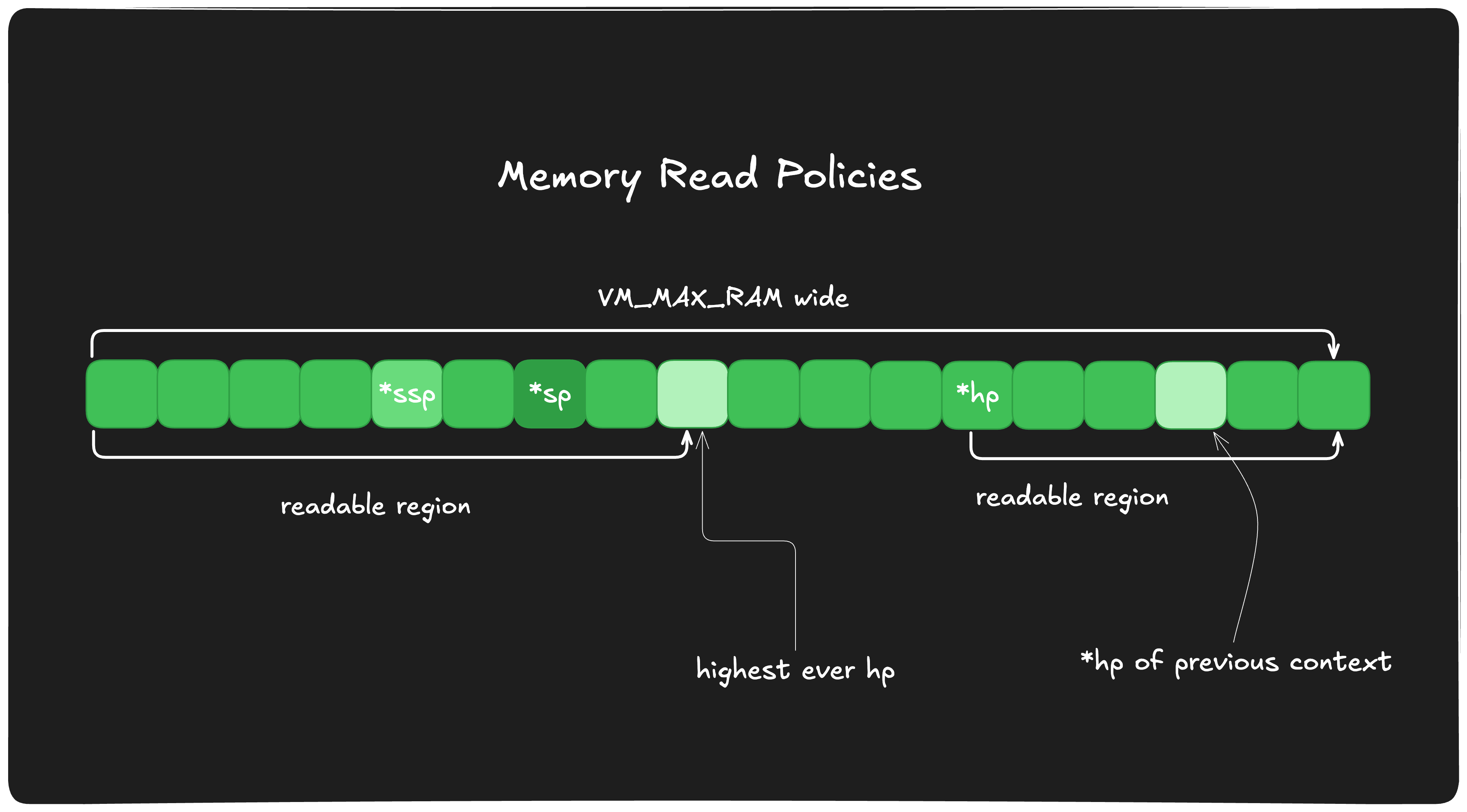

Read Policies for Context

A context can read any data from the stack in the range from the byte at index 0 (i.e., from the start of the memory ) to the highest ever $sp and between the current $hp and VM_MAX_RAM (i.e., until the end of the memory ) of the previous context that created the current context.

Any attempt to read from the region between the highest ever $sp during the context execution and the current $hp will return an error.

What do we mean by the highest ever $sp?

Since the stack can be grown and shrunk in size, it is possible that during the execution of some context, the $sp went until, for example, index 1000, but then elements were popped out of the stack, and now the current $sp is 900. In this scenario, the highest ever $sp during the execution of this call context is 1000, and hence, the memory region until 1000 is readable for the stack!

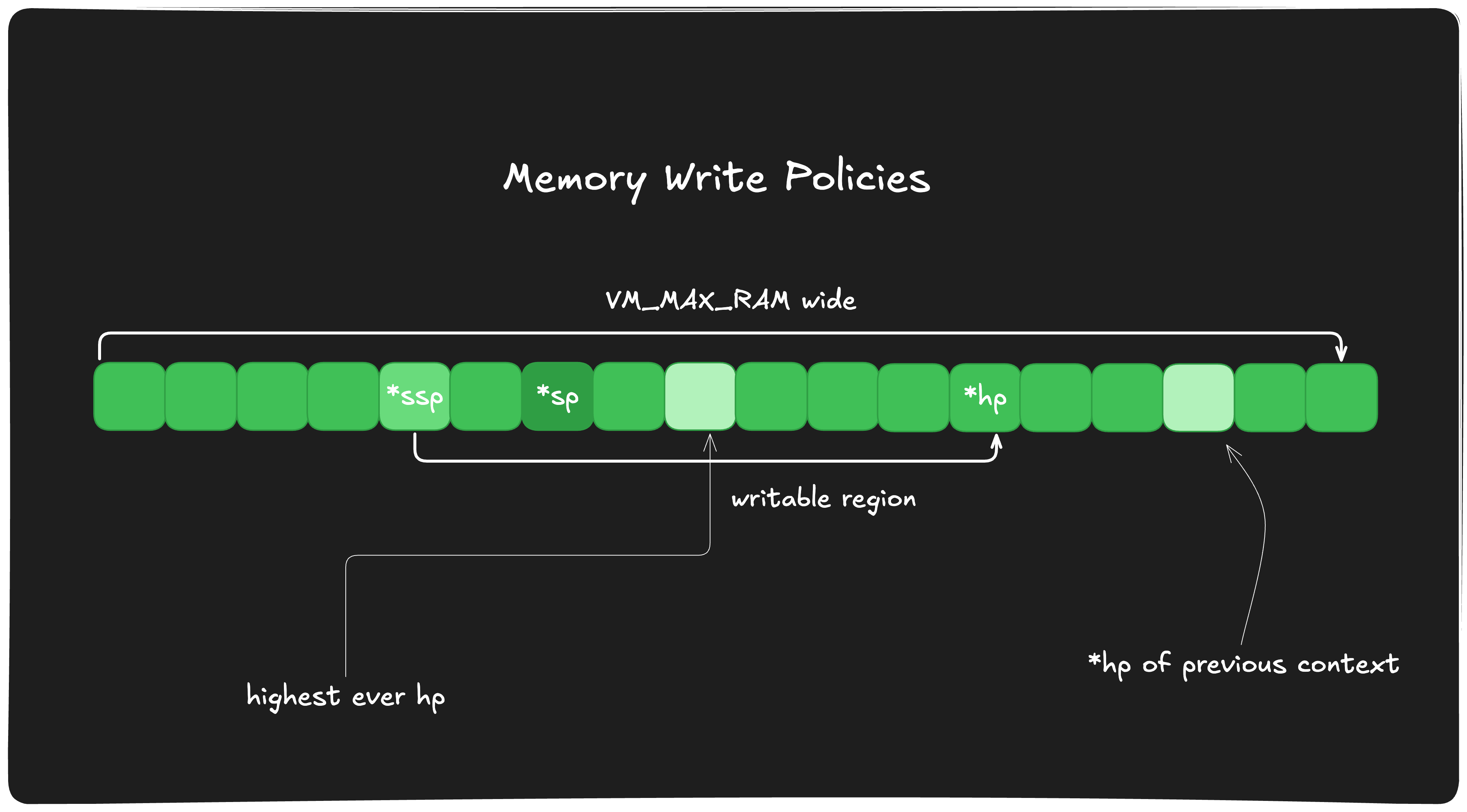

Write Policies for Context

A given context can write to any region between its $ssp and current $hp; hence, that memory region can be allocated and used for writing data.

Before writing to this memory region, allocate the bytes first. In the case of a stack, this is done using CFE and CFEI opcodes, while in the case of the heap, it is done via an ALOC opcode.

Note: Remember that once a context completes, all values on the stack (i.e., the call frame and all values allocated on the stack during execution ) are wiped down. Still, heap allocation stays, and the following context can only write data below the $hp of the existing context.

VM Initialization & Configuration

Configuration

The VM can be configured by setting the following parameters:

| name | type | value | note |

|---|---|---|---|

| CONTRACT_MAX_SIZE | uint64 | Maximum contract size, in bytes. | |

| VM_MAX_RAM | uint64 | 2**26 | 64 MiB. |

| MESSAGE_MAX_DATA_SIZE | uint64 | Maximum size of message data, in bytes. |

VM Initialization

This section outlines the process during VM initialization for every VM run. To initialize the VM, the following pushes to the stack sequentially:

-

Transaction hash (byte[32], word-aligned), computed as defined here .

-

Base asset ID (byte[32], word-aligned)

-

MAX_INPUTS pairs of (asset_id: byte[32], balance: uint64), of:

-

For predicate estimation and predicate verification , zeroes.

-

For script execution , the free balance for each asset ID seen in the transaction's inputs is ordered in ascending order. If there are fewer than MAX_INPUTS asset IDs, the pair has a zero value.

-

-

Transaction length, in bytes (uint64, word-aligned).

-

The transaction, serialized .

The following registers are then initialized (without explicit initialization, all registers are initialized to zero):

-

$ssp = 32 + 32 + MAX_INPUTS*(32+8) + size(tx)): the writable stack area starts immediately after the serialized transaction in memory (see above). -

$sp = $ssp:writable stack area is empty to start. -

$hp = VM_MAX_RAM:the heap area begins at the top and is empty to start.

Further Readings

- Nick Dodson’s tweet on what makes FuelVM unique: https://x.com/IAmNickDodson/status/1542516357886988288

- Blockchain Capital’s blog on FuelVM and Sway: https://medium.com/blockchain-capital-blog/exploring-the-fuelvm-86cf9ccdc159

- UTXO Model by River.com: https://river.com/learn/bitcoins-utxo-model/